/GUIDE.md

https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep · Markdown · 1008 lines · 809 code · 199 blank · 0 comment · 0 complexity · 628c840f16bd468a31fca49755fe30dc MD5 · raw file

- ## User Guide

- This guide is intended to give an elementary description of ripgrep and an

- overview of its capabilities. This guide assumes that ripgrep is

- [installed](README.md#installation)

- and that readers have passing familiarity with using command line tools. This

- also assumes a Unix-like system, although most commands are probably easily

- translatable to any command line shell environment.

- ### Table of Contents

- * [Basics](#basics)

- * [Recursive search](#recursive-search)

- * [Automatic filtering](#automatic-filtering)

- * [Manual filtering: globs](#manual-filtering-globs)

- * [Manual filtering: file types](#manual-filtering-file-types)

- * [Replacements](#replacements)

- * [Configuration file](#configuration-file)

- * [File encoding](#file-encoding)

- * [Binary data](#binary-data)

- * [Preprocessor](#preprocessor)

- * [Common options](#common-options)

- ### Basics

- ripgrep is a command line tool that searches your files for patterns that

- you give it. ripgrep behaves as if reading each file line by line. If a line

- matches the pattern provided to ripgrep, then that line will be printed. If a

- line does not match the pattern, then the line is not printed.

- The best way to see how this works is with an example. To show an example, we

- need something to search. Let's try searching ripgrep's source code. First

- grab a ripgrep source archive from

- https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep/archive/0.7.1.zip

- and extract it:

- ```

- $ curl -LO https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep/archive/0.7.1.zip

- $ unzip 0.7.1.zip

- $ cd ripgrep-0.7.1

- $ ls

- benchsuite grep tests Cargo.toml LICENSE-MIT

- ci ignore wincolor CHANGELOG.md README.md

- complete pkg appveyor.yml compile snapcraft.yaml

- doc src build.rs COPYING UNLICENSE

- globset termcolor Cargo.lock HomebrewFormula

- ```

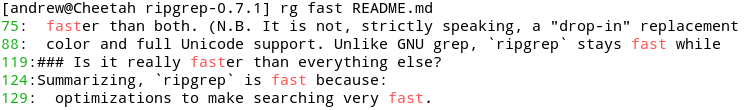

- Let's try our first search by looking for all occurrences of the word `fast`

- in `README.md`:

- ```

- $ rg fast README.md

- 75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

- 88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast while

- 119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

- 124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast because:

- 129: optimizations to make searching very fast.

- ```

- (**Note:** If you see an error message from ripgrep saying that it didn't

- search any files, then re-run ripgrep with the `--debug` flag. One likely cause

- of this is that you have a `*` rule in a `$HOME/.gitignore` file.)

- So what happened here? ripgrep read the contents of `README.md`, and for each

- line that contained `fast`, ripgrep printed it to your terminal. ripgrep also

- included the line number for each line by default. If your terminal supports

- colors, then your output might actually look something like this screenshot:

- [](https://burntsushi.net/stuff/ripgrep-guide-sample.png)

- In this example, we searched for something called a "literal" string. This

- means that our pattern was just some normal text that we asked ripgrep to

- find. But ripgrep supports the ability to specify patterns via [regular

- expressions](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regular_expression). As an example,

- what if we wanted to find all lines have a word that contains `fast` followed

- by some number of other letters?

- ```

- $ rg 'fast\w+' README.md

- 75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

- 119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

- ```

- In this example, we used the pattern `fast\w+`. This pattern tells ripgrep to

- look for any lines containing the letters `fast` followed by *one or more*

- word-like characters. Namely, `\w` matches characters that compose words (like

- `a` and `L` but unlike `.` and ` `). The `+` after the `\w` means, "match the

- previous pattern one or more times." This means that the word `fast` won't

- match because there are no word characters following the final `t`. But a word

- like `faster` will. `faste` would also match!

- Here's a different variation on this same theme:

- ```

- $ rg 'fast\w*' README.md

- 75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

- 88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast while

- 119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

- 124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast because:

- 129: optimizations to make searching very fast.

- ```

- In this case, we used `fast\w*` for our pattern instead of `fast\w+`. The `*`

- means that it should match *zero* or more times. In this case, ripgrep will

- print the same lines as the pattern `fast`, but if your terminal supports

- colors, you'll notice that `faster` will be highlighted instead of just the

- `fast` prefix.

- It is beyond the scope of this guide to provide a full tutorial on regular

- expressions, but ripgrep's specific syntax is documented here:

- https://docs.rs/regex/*/regex/#syntax

- ### Recursive search

- In the previous section, we showed how to use ripgrep to search a single file.

- In this section, we'll show how to use ripgrep to search an entire directory

- of files. In fact, *recursively* searching your current working directory is

- the default mode of operation for ripgrep, which means doing this is very

- simple.

- Using our unzipped archive of ripgrep source code, here's how to find all

- function definitions whose name is `write`:

- ```

- $ rg 'fn write\('

- src/printer.rs

- 469: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) {

- termcolor/src/lib.rs

- 227: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 250: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 428: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> { self.wtr.write(b) }

- 441: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> { self.wtr.write(b) }

- 454: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 511: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 848: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 915: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 949: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 1114: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 1348: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- 1353: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

- ```

- (**Note:** We escape the `(` here because `(` has special significance inside

- regular expressions. You could also use `rg -F 'fn write('` to achieve the

- same thing, where `-F` interprets your pattern as a literal string instead of

- a regular expression.)

- In this example, we didn't specify a file at all. Instead, ripgrep defaulted

- to searching your current directory in the absence of a path. In general,

- `rg foo` is equivalent to `rg foo ./`.

- This particular search showed us results in both the `src` and `termcolor`

- directories. The `src` directory is the core ripgrep code where as `termcolor`

- is a dependency of ripgrep (and is used by other tools). What if we only wanted

- to search core ripgrep code? Well, that's easy, just specify the directory you

- want:

- ```

- $ rg 'fn write\(' src

- src/printer.rs

- 469: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) {

- ```

- Here, ripgrep limited its search to the `src` directory. Another way of doing

- this search would be to `cd` into the `src` directory and simply use `rg 'fn

- write\('` again.

- ### Automatic filtering

- After recursive search, ripgrep's most important feature is what it *doesn't*

- search. By default, when you search a directory, ripgrep will ignore all of

- the following:

- 1. Files and directories that match the rules in your `.gitignore` glob

- pattern.

- 2. Hidden files and directories.

- 3. Binary files. (ripgrep considers any file with a `NUL` byte to be binary.)

- 4. Symbolic links aren't followed.

- All of these things can be toggled using various flags provided by ripgrep:

- 1. You can disable `.gitignore` handling with the `--no-ignore` flag.

- 2. Hidden files and directories can be searched with the `--hidden` flag.

- 3. Binary files can be searched via the `--text` (`-a` for short) flag.

- Be careful with this flag! Binary files may emit control characters to your

- terminal, which might cause strange behavior.

- 4. ripgrep can follow symlinks with the `--follow` (`-L` for short) flag.

- As a special convenience, ripgrep also provides a flag called `--unrestricted`

- (`-u` for short). Repeated uses of this flag will cause ripgrep to disable

- more and more of its filtering. That is, `-u` will disable `.gitignore`

- handling, `-uu` will search hidden files and directories and `-uuu` will search

- binary files. This is useful when you're using ripgrep and you aren't sure

- whether its filtering is hiding results from you. Tacking on a couple `-u`

- flags is a quick way to find out. (Use the `--debug` flag if you're still

- perplexed, and if that doesn't help,

- [file an issue](https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep/issues/new).)

- ripgrep's `.gitignore` handling actually goes a bit beyond just `.gitignore`

- files. ripgrep will also respect repository specific rules found in

- `$GIT_DIR/info/exclude`, as well as any global ignore rules in your

- `core.excludesFile` (which is usually `$XDG_CONFIG_HOME/git/ignore` on

- Unix-like systems).

- Sometimes you want to search files that are in your `.gitignore`, so it is

- possible to specify additional ignore rules or overrides in a `.ignore`

- (application agnostic) or `.rgignore` (ripgrep specific) file.

- For example, let's say you have a `.gitignore` file that looks like this:

- ```

- log/

- ```

- This generally means that any `log` directory won't be tracked by `git`.

- However, perhaps it contains useful output that you'd like to include in your

- searches, but you still don't want to track it in `git`. You can achieve this

- by creating a `.ignore` file in the same directory as the `.gitignore` file

- with the following contents:

- ```

- !log/

- ```

- ripgrep treats `.ignore` files with higher precedence than `.gitignore` files

- (and treats `.rgignore` files with higher precedence than `.ignore` files).

- This means ripgrep will see the `!log/` whitelist rule first and search that

- directory.

- Like `.gitignore`, a `.ignore` file can be placed in any directory. Its rules

- will be processed with respect to the directory it resides in, just like

- `.gitignore`.

- To process `.gitignore` and `.ignore` files case insensitively, use the flag

- `--ignore-file-case-insensitive`. This is especially useful on case insensitive

- file systems like those on Windows and macOS. Note though that this can come

- with a significant performance penalty, and is therefore disabled by default.

- For a more in depth description of how glob patterns in a `.gitignore` file

- are interpreted, please see `man gitignore`.

- ### Manual filtering: globs

- In the previous section, we talked about ripgrep's filtering that it does by

- default. It is "automatic" because it reacts to your environment. That is, it

- uses already existing `.gitignore` files to produce more relevant search

- results.

- In addition to automatic filtering, ripgrep also provides more manual or ad hoc

- filtering. This comes in two varieties: additional glob patterns specified in

- your ripgrep commands and file type filtering. This section covers glob

- patterns while the next section covers file type filtering.

- In our ripgrep source code (see [Basics](#basics) for instructions on how to

- get a source archive to search), let's say we wanted to see which things depend

- on `clap`, our argument parser.

- We could do this:

- ```

- $ rg clap

- [lots of results]

- ```

- But this shows us many things, and we're only interested in where we wrote

- `clap` as a dependency. Instead, we could limit ourselves to TOML files, which

- is how dependencies are communicated to Rust's build tool, Cargo:

- ```

- $ rg clap -g '*.toml'

- Cargo.toml

- 35:clap = "2.26"

- 51:clap = "2.26"

- ```

- The `-g '*.toml'` syntax says, "make sure every file searched matches this

- glob pattern." Note that we put `'*.toml'` in single quotes to prevent our

- shell from expanding the `*`.

- If we wanted, we could tell ripgrep to search anything *but* `*.toml` files:

- ```

- $ rg clap -g '!*.toml'

- [lots of results]

- ```

- This will give you a lot of results again as above, but they won't include

- files ending with `.toml`. Note that the use of a `!` here to mean "negation"

- is a bit non-standard, but it was chosen to be consistent with how globs in

- `.gitignore` files are written. (Although, the meaning is reversed. In

- `.gitignore` files, a `!` prefix means whitelist, and on the command line, a

- `!` means blacklist.)

- Globs are interpreted in exactly the same way as `.gitignore` patterns. That

- is, later globs will override earlier globs. For example, the following command

- will search only `*.toml` files:

- ```

- $ rg clap -g '!*.toml' -g '*.toml'

- ```

- Interestingly, reversing the order of the globs in this case will match

- nothing, since the presence of at least one non-blacklist glob will institute a

- requirement that every file searched must match at least one glob. In this

- case, the blacklist glob takes precedence over the previous glob and prevents

- any file from being searched at all!

- ### Manual filtering: file types

- Over time, you might notice that you use the same glob patterns over and over.

- For example, you might find yourself doing a lot of searches where you only

- want to see results for Rust files:

- ```

- $ rg 'fn run' -g '*.rs'

- ```

- Instead of writing out the glob every time, you can use ripgrep's support for

- file types:

- ```

- $ rg 'fn run' --type rust

- ```

- or, more succinctly,

- ```

- $ rg 'fn run' -trust

- ```

- The way the `--type` flag functions is simple. It acts as a name that is

- assigned to one or more globs that match the relevant files. This lets you

- write a single type that might encompass a broad range of file extensions. For

- example, if you wanted to search C files, you'd have to check both C source

- files and C header files:

- ```

- $ rg 'int main' -g '*.{c,h}'

- ```

- or you could just use the C file type:

- ```

- $ rg 'int main' -tc

- ```

- Just as you can write blacklist globs, you can blacklist file types too:

- ```

- $ rg clap --type-not rust

- ```

- or, more succinctly,

- ```

- $ rg clap -Trust

- ```

- That is, `-t` means "include files of this type" where as `-T` means "exclude

- files of this type."

- To see the globs that make up a type, run `rg --type-list`:

- ```

- $ rg --type-list | rg '^make:'

- make: *.mak, *.mk, GNUmakefile, Gnumakefile, Makefile, gnumakefile, makefile

- ```

- By default, ripgrep comes with a bunch of pre-defined types. Generally, these

- types correspond to well known public formats. But you can define your own

- types as well. For example, perhaps you frequently search "web" files, which

- consist of Javascript, HTML and CSS:

- ```

- $ rg --type-add 'web:*.html' --type-add 'web:*.css' --type-add 'web:*.js' -tweb title

- ```

- or, more succinctly,

- ```

- $ rg --type-add 'web:*.{html,css,js}' -tweb title

- ```

- The above command defines a new type, `web`, corresponding to the glob

- `*.{html,css,js}`. It then applies the new filter with `-tweb` and searches for

- the pattern `title`. If you ran

- ```

- $ rg --type-add 'web:*.{html,css,js}' --type-list

- ```

- Then you would see your `web` type show up in the list, even though it is not

- part of ripgrep's built-in types.

- It is important to stress here that the `--type-add` flag only applies to the

- current command. It does not add a new file type and save it somewhere in a

- persistent form. If you want a type to be available in every ripgrep command,

- then you should either create a shell alias:

- ```

- alias rg="rg --type-add 'web:*.{html,css,js}'"

- ```

- or add `--type-add=web:*.{html,css,js}` to your ripgrep configuration file.

- ([Configuration files](#configuration-file) are covered in more detail later.)

- #### The special `all` file type

- A special option supported by the `--type` flag is `all`. `--type all` looks

- for a match in any of the supported file types listed by `--type-list`,

- including those added on the command line using `--type-add`. It's equivalent

- to the command `rg --type agda --type asciidoc --type asm ...`, where `...`

- stands for a list of `--type` flags for the rest of the types in `--type-list`.

- As an example, let's suppose you have a shell script in your current directory,

- `my-shell-script`, which includes a shell library, `my-shell-library.bash`.

- Both `rg --type sh` and `rg --type all` would only search for matches in

- `my-shell-library.bash`, not `my-shell-script`, because the globs matched

- by the `sh` file type don't include files without an extension. On the

- other hand, `rg --type-not all` would search `my-shell-script` but not

- `my-shell-library.bash`.

- ### Replacements

- ripgrep provides a limited ability to modify its output by replacing matched

- text with some other text. This is easiest to explain with an example. Remember

- when we searched for the word `fast` in ripgrep's README?

- ```

- $ rg fast README.md

- 75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

- 88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast while

- 119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

- 124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast because:

- 129: optimizations to make searching very fast.

- ```

- What if we wanted to *replace* all occurrences of `fast` with `FAST`? That's

- easy with ripgrep's `--replace` flag:

- ```

- $ rg fast README.md --replace FAST

- 75: FASTer than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

- 88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays FAST while

- 119:### Is it really FASTer than everything else?

- 124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is FAST because:

- 129: optimizations to make searching very FAST.

- ```

- or, more succinctly,

- ```

- $ rg fast README.md -r FAST

- [snip]

- ```

- In essence, the `--replace` flag applies *only* to the matching portion of text

- in the output. If you instead wanted to replace an entire line of text, then

- you need to include the entire line in your match. For example:

- ```

- $ rg '^.*fast.*$' README.md -r FAST

- 75:FAST

- 88:FAST

- 119:FAST

- 124:FAST

- 129:FAST

- ```

- Alternatively, you can combine the `--only-matching` (or `-o` for short) with

- the `--replace` flag to achieve the same result:

- ```

- $ rg fast README.md --only-matching --replace FAST

- 75:FAST

- 88:FAST

- 119:FAST

- 124:FAST

- 129:FAST

- ```

- or, more succinctly,

- ```

- $ rg fast README.md -or FAST

- [snip]

- ```

- Finally, replacements can include capturing groups. For example, let's say

- we wanted to find all occurrences of `fast` followed by another word and

- join them together with a dash. The pattern we might use for that is

- `fast\s+(\w+)`, which matches `fast`, followed by any amount of whitespace,

- followed by any number of "word" characters. We put the `\w+` in a "capturing

- group" (indicated by parentheses) so that we can reference it later in our

- replacement string. For example:

- ```

- $ rg 'fast\s+(\w+)' README.md -r 'fast-$1'

- 88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast-while

- 124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast-because:

- ```

- Our replacement string here, `fast-$1`, consists of `fast-` followed by the

- contents of the capturing group at index `1`. (Capturing groups actually start

- at index 0, but the `0`th capturing group always corresponds to the entire

- match. The capturing group at index `1` always corresponds to the first

- explicit capturing group found in the regex pattern.)

- Capturing groups can also be named, which is sometimes more convenient than

- using the indices. For example, the following command is equivalent to the

- above command:

- ```

- $ rg 'fast\s+(?P<word>\w+)' README.md -r 'fast-$word'

- 88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast-while

- 124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast-because:

- ```

- It is important to note that ripgrep **will never modify your files**. The

- `--replace` flag only controls ripgrep's output. (And there is no flag to let

- you do a replacement in a file.)

- ### Configuration file

- It is possible that ripgrep's default options aren't suitable in every case.

- For that reason, and because shell aliases aren't always convenient, ripgrep

- supports configuration files.

- Setting up a configuration file is simple. ripgrep will not look in any

- predetermined directory for a config file automatically. Instead, you need to

- set the `RIPGREP_CONFIG_PATH` environment variable to the file path of your

- config file. Once the environment variable is set, open the file and just type

- in the flags you want set automatically. There are only two rules for

- describing the format of the config file:

- 1. Every line is a shell argument, after trimming whitespace.

- 2. Lines starting with `#` (optionally preceded by any amount of whitespace)

- are ignored.

- In particular, there is no escaping. Each line is given to ripgrep as a single

- command line argument verbatim.

- Here's an example of a configuration file, which demonstrates some of the

- formatting peculiarities:

- ```

- $ cat $HOME/.ripgreprc

- # Don't let ripgrep vomit really long lines to my terminal, and show a preview.

- --max-columns=150

- --max-columns-preview

- # Add my 'web' type.

- --type-add

- web:*.{html,css,js}*

- # Using glob patterns to include/exclude files or folders

- --glob=!git/*

- # or

- --glob

- !git/*

- # Set the colors.

- --colors=line:none

- --colors=line:style:bold

- # Because who cares about case!?

- --smart-case

- ```

- When we use a flag that has a value, we either put the flag and the value on

- the same line but delimited by an `=` sign (e.g., `--max-columns=150`), or we

- put the flag and the value on two different lines. This is because ripgrep's

- argument parser knows to treat the single argument `--max-columns=150` as a

- flag with a value, but if we had written `--max-columns 150` in our

- configuration file, then ripgrep's argument parser wouldn't know what to do

- with it.

- Putting the flag and value on different lines is exactly equivalent and is a

- matter of style.

- Comments are encouraged so that you remember what the config is doing. Empty

- lines are OK too.

- So let's say you're using the above configuration file, but while you're at a

- terminal, you really want to be able to see lines longer than 150 columns. What

- do you do? Thankfully, all you need to do is pass `--max-columns 0` (or `-M0`

- for short) on the command line, which will override your configuration file's

- setting. This works because ripgrep's configuration file is *prepended* to the

- explicit arguments you give it on the command line. Since flags given later

- override flags given earlier, everything works as expected. This works for most

- other flags as well, and each flag's documentation states which other flags

- override it.

- If you're confused about what configuration file ripgrep is reading arguments

- from, then running ripgrep with the `--debug` flag should help clarify things.

- The debug output should note what config file is being loaded and the arguments

- that have been read from the configuration.

- Finally, if you want to make absolutely sure that ripgrep *isn't* reading a

- configuration file, then you can pass the `--no-config` flag, which will always

- prevent ripgrep from reading extraneous configuration from the environment,

- regardless of what other methods of configuration are added to ripgrep in the

- future.

- ### File encoding

- [Text encoding](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Character_encoding) is a complex

- topic, but we can try to summarize its relevancy to ripgrep:

- * Files are generally just a bundle of bytes. There is no reliable way to know

- their encoding.

- * Either the encoding of the pattern must match the encoding of the files being

- searched, or a form of transcoding must be performed that converts either the

- pattern or the file to the same encoding as the other.

- * ripgrep tends to work best on plain text files, and among plain text files,

- the most popular encodings likely consist of ASCII, latin1 or UTF-8. As

- a special exception, UTF-16 is prevalent in Windows environments

- In light of the above, here is how ripgrep behaves when `--encoding auto` is

- given, which is the default:

- * All input is assumed to be ASCII compatible (which means every byte that

- corresponds to an ASCII codepoint actually is an ASCII codepoint). This

- includes ASCII itself, latin1 and UTF-8.

- * ripgrep works best with UTF-8. For example, ripgrep's regular expression

- engine supports Unicode features. Namely, character classes like `\w` will

- match all word characters by Unicode's definition and `.` will match any

- Unicode codepoint instead of any byte. These constructions assume UTF-8,

- so they simply won't match when they come across bytes in a file that aren't

- UTF-8.

- * To handle the UTF-16 case, ripgrep will do something called "BOM sniffing"

- by default. That is, the first three bytes of a file will be read, and if

- they correspond to a UTF-16 BOM, then ripgrep will transcode the contents of

- the file from UTF-16 to UTF-8, and then execute the search on the transcoded

- version of the file. (This incurs a performance penalty since transcoding

- is slower than regex searching.) If the file contains invalid UTF-16, then

- the Unicode replacement codepoint is substituted in place of invalid code

- units.

- * To handle other cases, ripgrep provides a `-E/--encoding` flag, which permits

- you to specify an encoding from the

- [Encoding Standard](https://encoding.spec.whatwg.org/#concept-encoding-get).

- ripgrep will assume *all* files searched are the encoding specified (unless

- the file has a BOM) and will perform a transcoding step just like in the

- UTF-16 case described above.

- By default, ripgrep will not require its input be valid UTF-8. That is, ripgrep

- can and will search arbitrary bytes. The key here is that if you're searching

- content that isn't UTF-8, then the usefulness of your pattern will degrade. If

- you're searching bytes that aren't ASCII compatible, then it's likely the

- pattern won't find anything. With all that said, this mode of operation is

- important, because it lets you find ASCII or UTF-8 *within* files that are

- otherwise arbitrary bytes.

- As a special case, the `-E/--encoding` flag supports the value `none`, which

- will completely disable all encoding related logic, including BOM sniffing.

- When `-E/--encoding` is set to `none`, ripgrep will search the raw bytes of

- the underlying file with no transcoding step. For example, here's how you might

- search the raw UTF-16 encoding of the string `Шерлок`:

- ```

- $ rg '(?-u)\(\x045\x04@\x04;\x04>\x04:\x04' -E none -a some-utf16-file

- ```

- Of course, that's just an example meant to show how one can drop down into

- raw bytes. Namely, the simpler command works as you might expect automatically:

- ```

- $ rg 'Шерлок' some-utf16-file

- ```

- Finally, it is possible to disable ripgrep's Unicode support from within the

- regular expression. For example, let's say you wanted `.` to match any byte

- rather than any Unicode codepoint. (You might want this while searching a

- binary file, since `.` by default will not match invalid UTF-8.) You could do

- this by disabling Unicode via a regular expression flag:

- ```

- $ rg '(?-u:.)'

- ```

- This works for any part of the pattern. For example, the following will find

- any Unicode word character followed by any ASCII word character followed by

- another Unicode word character:

- ```

- $ rg '\w(?-u:\w)\w'

- ```

- ### Binary data

- In addition to skipping hidden files and files in your `.gitignore` by default,

- ripgrep also attempts to skip binary files. ripgrep does this by default

- because binary files (like PDFs or images) are typically not things you want to

- search when searching for regex matches. Moreover, if content in a binary file

- did match, then it's possible for undesirable binary data to be printed to your

- terminal and wreak havoc.

- Unfortunately, unlike skipping hidden files and respecting your `.gitignore`

- rules, a file cannot as easily be classified as binary. In order to figure out

- whether a file is binary, the most effective heuristic that balances

- correctness with performance is to simply look for `NUL` bytes. At that point,

- the determination is simple: a file is considered "binary" if and only if it

- contains a `NUL` byte somewhere in its contents.

- The issue is that while most binary files will have a `NUL` byte toward the

- beginning of its contents, this is not necessarily true. The `NUL` byte might

- be the very last byte in a large file, but that file is still considered

- binary. While this leads to a fair amount of complexity inside ripgrep's

- implementation, it also results in some unintuitive user experiences.

- At a high level, ripgrep operates in three different modes with respect to

- binary files:

- 1. The default mode is to attempt to remove binary files from a search

- completely. This is meant to mirror how ripgrep removes hidden files and

- files in your `.gitignore` automatically. That is, as soon as a file is

- detected as binary, searching stops. If a match was already printed (because

- it was detected long before a `NUL` byte), then ripgrep will print a warning

- message indicating that the search stopped prematurely. This default mode

- **only applies to files searched by ripgrep as a result of recursive

- directory traversal**, which is consistent with ripgrep's other automatic

- filtering. For example, `rg foo .file` will search `.file` even though it

- is hidden. Similarly, `rg foo binary-file` will search `binary-file` in

- "binary" mode automatically.

- 2. Binary mode is similar to the default mode, except it will not always

- stop searching after it sees a `NUL` byte. Namely, in this mode, ripgrep

- will continue searching a file that is known to be binary until the first

- of two conditions is met: 1) the end of the file has been reached or 2) a

- match is or has been seen. This means that in binary mode, if ripgrep

- reports no matches, then there are no matches in the file. When a match does

- occur, ripgrep prints a message similar to one it prints when in its default

- mode indicating that the search has stopped prematurely. This mode can be

- forcefully enabled for all files with the `--binary` flag. The purpose of

- binary mode is to provide a way to discover matches in all files, but to

- avoid having binary data dumped into your terminal.

- 3. Text mode completely disables all binary detection and searches all files

- as if they were text. This is useful when searching a file that is

- predominantly text but contains a `NUL` byte, or if you are specifically

- trying to search binary data. This mode can be enabled with the `-a/--text`

- flag. Note that when using this mode on very large binary files, it is

- possible for ripgrep to use a lot of memory.

- Unfortunately, there is one additional complexity in ripgrep that can make it

- difficult to reason about binary files. That is, the way binary detection works

- depends on the way that ripgrep searches your files. Specifically:

- * When ripgrep uses memory maps, then binary detection is only performed on the

- first few kilobytes of the file in addition to every matching line.

- * When ripgrep doesn't use memory maps, then binary detection is performed on

- all bytes searched.

- This means that whether a file is detected as binary or not can change based

- on the internal search strategy used by ripgrep. If you prefer to keep

- ripgrep's binary file detection consistent, then you can disable memory maps

- via the `--no-mmap` flag. (The cost will be a small performance regression when

- searching very large files on some platforms.)

- ### Preprocessor

- In ripgrep, a preprocessor is any type of command that can be run to transform

- the input of every file before ripgrep searches it. This makes it possible to

- search virtually any kind of content that can be automatically converted to

- text without having to teach ripgrep how to read said content.

- One common example is searching PDFs. PDFs are first and foremost meant to be

- displayed to users. But PDFs often have text streams in them that can be useful

- to search. In our case, we want to search Bruce Watson's excellent

- dissertation,

- [Taxonomies and Toolkits of Regular Language Algorithms](https://burntsushi.net/stuff/1995-watson.pdf).

- After downloading it, let's try searching it:

- ```

- $ rg 'The Commentz-Walter algorithm' 1995-watson.pdf

- $

- ```

- Surely, a dissertation on regular language algorithms would mention

- Commentz-Walter. Indeed it does, but our search isn't picking it up because

- PDFs are a binary format, and the text shown in the PDF may not be encoded as

- simple contiguous UTF-8. Namely, even passing the `-a/--text` flag to ripgrep

- will not make our search work.

- One way to fix this is to convert the PDF to plain text first. This won't work

- well for all PDFs, but does great in a lot of cases. (Note that the tool we

- use, `pdftotext`, is part of the [poppler](https://poppler.freedesktop.org)

- PDF rendering library.)

- ```

- $ pdftotext 1995-watson.pdf > 1995-watson.txt

- $ rg 'The Commentz-Walter algorithm' 1995-watson.txt

- 316:The Commentz-Walter algorithms : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :

- 7165:4.4 The Commentz-Walter algorithms

- 10062:in input string S , we obtain the Boyer-Moore algorithm. The Commentz-Walter algorithm

- 17218:The Commentz-Walter algorithm (and its variants) displayed more interesting behaviour,

- 17249:Aho-Corasick algorithms are used extensively. The Commentz-Walter algorithms are used

- 17297: The Commentz-Walter algorithms (CW). In all versions of the CW algorithms, a common program skeleton is used with di erent shift functions. The CW algorithms are

- ```

- But having to explicitly convert every file can be a pain, especially when you

- have a directory full of PDF files. Instead, we can use ripgrep's preprocessor

- feature to search the PDF. ripgrep's `--pre` flag works by taking a single

- command name and then executing that command for every file that it searches.

- ripgrep passes the file path as the first and only argument to the command and

- also sends the contents of the file to stdin. So let's write a simple shell

- script that wraps `pdftotext` in a way that conforms to this interface:

- ```

- $ cat preprocess

- #!/bin/sh

- exec pdftotext - -

- ```

- With `preprocess` in the same directory as `1995-watson.pdf`, we can now use it

- to search the PDF:

- ```

- $ rg --pre ./preprocess 'The Commentz-Walter algorithm' 1995-watson.pdf

- 316:The Commentz-Walter algorithms : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :

- 7165:4.4 The Commentz-Walter algorithms

- 10062:in input string S , we obtain the Boyer-Moore algorithm. The Commentz-Walter algorithm

- 17218:The Commentz-Walter algorithm (and its variants) displayed more interesting behaviour,

- 17249:Aho-Corasick algorithms are used extensively. The Commentz-Walter algorithms are used

- 17297: The Commentz-Walter algorithms (CW). In all versions of the CW algorithms, a common program skeleton is used with di erent shift functions. The CW algorithms are

- ```

- Note that `preprocess` must be resolvable to a command that ripgrep can read.

- The simplest way to do this is to put your preprocessor command in a directory

- that is in your `PATH` (or equivalent), or otherwise use an absolute path.

- As a bonus, this turns out to be quite a bit faster than other specialized PDF

- grepping tools:

- ```

- $ time rg --pre ./preprocess 'The Commentz-Walter algorithm' 1995-watson.pdf -c

- 6

- real 0.697

- user 0.684

- sys 0.007

- maxmem 16 MB

- faults 0

- $ time pdfgrep 'The Commentz-Walter algorithm' 1995-watson.pdf -c

- 6

- real 1.336

- user 1.310

- sys 0.023

- maxmem 16 MB

- faults 0

- ```

- If you wind up needing to search a lot of PDFs, then ripgrep's parallelism can

- make the speed difference even greater.

- #### A more robust preprocessor

- One of the problems with the aforementioned preprocessor is that it will fail

- if you try to search a file that isn't a PDF:

- ```

- $ echo foo > not-a-pdf

- $ rg --pre ./preprocess 'The Commentz-Walter algorithm' not-a-pdf

- not-a-pdf: preprocessor command failed: '"./preprocess" "not-a-pdf"':

- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- Syntax Warning: May not be a PDF file (continuing anyway)

- Syntax Error: Couldn't find trailer dictionary

- Syntax Error: Couldn't find trailer dictionary

- Syntax Error: Couldn't read xref table

- ```

- To fix this, we can make our preprocessor script a bit more robust by only

- running `pdftotext` when we think the input is a non-empty PDF:

- ```

- $ cat preprocessor

- #!/bin/sh

- case "$1" in

- *.pdf)

- # The -s flag ensures that the file is non-empty.

- if [ -s "$1" ]; then

- exec pdftotext - -

- else

- exec cat

- fi

- ;;

- *)

- exec cat

- ;;

- esac

- ```

- We can even extend our preprocessor to search other kinds of files. Sometimes

- we don't always know the file type from the file name, so we can use the `file`

- utility to "sniff" the type of the file based on its contents:

- ```

- $ cat processor

- #!/bin/sh

- case "$1" in

- *.pdf)

- # The -s flag ensures that the file is non-empty.

- if [ -s "$1" ]; then

- exec pdftotext - -

- else

- exec cat

- fi

- ;;

- *)

- case $(file "$1") in

- *Zstandard*)

- exec pzstd -cdq

- ;;

- *)

- exec cat

- ;;

- esac

- ;;

- esac

- ```

- #### Reducing preprocessor overhead

- There is one more problem with the above approach: it requires running a

- preprocessor for every single file that ripgrep searches. If every file needs

- a preprocessor, then this is OK. But if most don't, then this can substantially

- slow down searches because of the overhead of launching new processors. You

- can avoid this by telling ripgrep to only invoke the preprocessor when the file

- path matches a glob. For example, consider the performance difference even when

- searching a repository as small as ripgrep's:

- ```

- $ time rg --pre pre-rg 'fn is_empty' -c

- crates/globset/src/lib.rs:1

- crates/matcher/src/lib.rs:2

- crates/ignore/src/overrides.rs:1

- crates/ignore/src/gitignore.rs:1

- crates/ignore/src/types.rs:1

- real 0.138

- user 0.485

- sys 0.209

- maxmem 7 MB

- faults 0

- $ time rg --pre pre-rg --pre-glob '*.pdf' 'fn is_empty' -c

- crates/globset/src/lib.rs:1

- crates/ignore/src/types.rs:1

- crates/ignore/src/gitignore.rs:1

- crates/ignore/src/overrides.rs:1

- crates/matcher/src/lib.rs:2

- real 0.008

- user 0.010

- sys 0.002

- maxmem 7 MB

- faults 0

- ```

- ### Common options

- ripgrep has a lot of flags. Too many to keep in your head at once. This section

- is intended to give you a sampling of some of the most important and frequently

- used options that will likely impact how you use ripgrep on a regular basis.

- * `-h`: Show ripgrep's condensed help output.

- * `--help`: Show ripgrep's longer form help output. (Nearly what you'd find in

- ripgrep's man page, so pipe it into a pager!)

- * `-i/--ignore-case`: When searching for a pattern, ignore case differences.

- That is `rg -i fast` matches `fast`, `fASt`, `FAST`, etc.

- * `-S/--smart-case`: This is similar to `--ignore-case`, but disables itself

- if the pattern contains any uppercase letters. Usually this flag is put into

- alias or a config file.

- * `-w/--word-regexp`: Require that all matches of the pattern be surrounded

- by word boundaries. That is, given `pattern`, the `--word-regexp` flag will

- cause ripgrep to behave as if `pattern` were actually `\b(?:pattern)\b`.

- * `-c/--count`: Report a count of total matched lines.

- * `--files`: Print the files that ripgrep *would* search, but don't actually

- search them.

- * `-a/--text`: Search binary files as if they were plain text.

- * `-U/--multiline`: Permit matches to span multiple lines.

- * `-z/--search-zip`: Search compressed files (gzip, bzip2, lzma, xz, lz4,

- brotli, zstd). This is disabled by default.

- * `-C/--context`: Show the lines surrounding a match.

- * `--sort path`: Force ripgrep to sort its output by file name. (This disables

- parallelism, so it might be slower.)

- * `-L/--follow`: Follow symbolic links while recursively searching.

- * `-M/--max-columns`: Limit the length of lines printed by ripgrep.

- * `--debug`: Shows ripgrep's debug output. This is useful for understanding

- why a particular file might be ignored from search, or what kinds of

- configuration ripgrep is loading from the environment.